The apostrophe: why it’s confusing and how to master its mysteries

By Allen Palmer

Let’s explore why the apostrophe causes so much confusion and get some tips on how to avoid misusing it. It could help your career and possibly improve your love life. (Stay with me on this.)

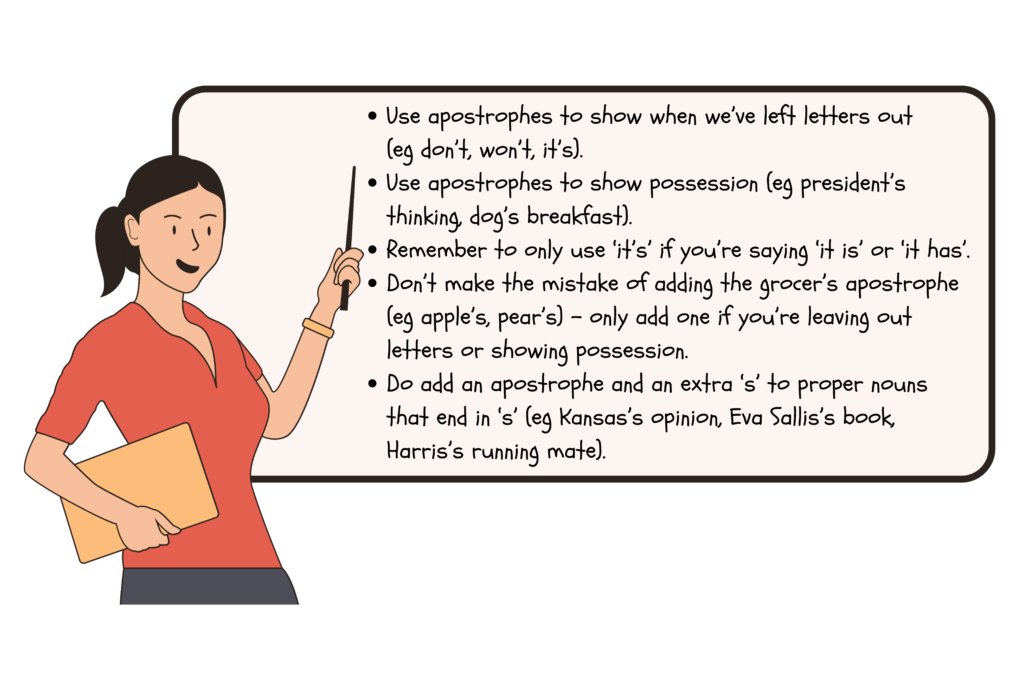

But first, a summary – in case you want to get to the punchline without reading to the end!

Should we feel embarrassed if we struggle with the apostrophe?

Robert Lawrence Trask, author of The Penguin Guide to Punctuation, said that ‘the apostrophe is the most troublesome punctuation mark in English … No other punctuation mark causes so much bewilderment.’

So, if you haven’t yet mastered it, there’s clearly no shame.

Why should we get better at using them?

Some employers admit to shredding job applications that include poor grammar, spelling and punctuation.

And research by the dating site OkCupid has concluded that ‘bad grammar and bad spelling are huge turn-offs’. It specifically cites the misuse of the apostrophe.

Now, I think bosses who cull applications based on punctuation might be missing out on some valuable employees. And the perfect partner could well have imperfect punctuation. So, on this issue, I’d like to encourage a little more generosity of spirit.

But the fact remains, if we make mistakes with our punctuation, some people will judge us, and I want to help you survive that cruel and unjust assessment.

Let’s begin by tracking down the source of the confusion.

Where did apostrophes come from?

Most attribute apostrophes to French printer Geoffroy Tory, who used them to show where letters had been left out.

This allowed the French to write ‘l’hôtel’ rather than ‘le hôtel’ when describing ‘the hotel’. And it made a lot of sense because it allowed written French to more closely match the way people spoke it.

So, the apostrophe began life meaning that something was missing, which is where its name came from. ‘Apostrophē’ is a Greek word for the rhetorical device where a speaker turns to address an absent person.

And this elision – a fancy word for leaving stuff out – streamlined things for us in English, too. We were then able to write:

- don’t rather than do not

- o’clock rather than of the clock

- it’s rather than it is or it has.

If apostrophes had stayed with this single purpose – to show omission – I wouldn’t have had to write this. But we started to use them for something else as well.

When did the confusion set in?

In the 17th or 18th century, we began using the apostrophe to show not just omission, but possession:

- Raheem’s car

- the president’s thinking

- a dog’s breakfast.

This way of showing possession is not unique to English, but it is rare. The romance languages, for example, would say ‘Raheem’s car’ like this:

- Italian: la macchina di Raheem

- French: la voiture de Raheem

- Spanish: el auto de Raheem.

Basically, ‘the car of Raheem’ rather than ‘Raheem’s car’.

Obviously, this innovation in English made for a more streamlined way to show possession, so you can see the attraction. But then we had a problem.

Why is using an apostrophe to show possession an issue?

It becomes a problem with ‘it’s’.

We’ve just said that we show possession by adding an apostrophe and the letter ‘s’, so why, in the title of this piece, does it say ‘its mysteries’?

Shouldn’t it be ‘it’s mysteries’ because the apostrophe possesses the mysteries? No. Not according to the current conventions. We could have a long discussion about why this is the convention, but let’s focus on the main game.

This is the convention, so how do we deal with it?

Simple. Whenever you write the letters ‘its’, ask yourself, am I saying, ‘it is’ or ‘it has’? If so, add an apostrophe to make it ‘it’s’. If not, leave out the apostrophe.

So, what other traps should we avoid? Adding apostrophes when they’re not needed, and showing possession when the word already ends in an ‘s’.

Let’s look at those now.

What is a grocer’s apostrophe?

This is general term to describe the common mistake of adding an apostrophe in any plural word, and it stems from seeing words like this when we go to get our fruit and veg:

- tomatoe’s

- apple’s

- pear’s.

But we also see the grocer’s apostrophe here:

- KPI’s

- photo’s

- UFO’s.

Why don’t they have an apostrophe? Apply the conventions we’ve just learned. Do they show omission? No. Do they show possession? No. No omission, no possession, no apostrophe.

How do we show possession when a word already ends in ‘s’?

Good question.

If we wanted to talk about the position that the US state of Kansas had on a particular subject, would we say ‘Kansas’ position’ or ‘Kansas’s position’?

You will not find a unanimous opinion on this. In fact, the 9 justices of the US Supreme Court could not agree on this. Five felt it should be ‘Kansas’ ’, while the other 4 dissented, feeling it should be ‘Kansas’s’.

We side with the minority. Why? Partly because you sound that extra ‘s’ when you say it. But also because it’s what the Australian Style Guide™ tells us to do. It says that for proper nouns ending in the letter ‘s’, we ‘can simply add an apostrophe and ‘s’ at the end’.

Where can you get more advice about apostrophes and the like?

For more support, check out our free Australian Style Guide. This resource will help make your writing clear, consistent and error free, with advice about:

- language

- people and places

- numbers

- punctuation

- formatting

- referencing.

And for clear communication techniques that speed up decision-making, streamline processes and avoid confusion, contact us about our ISO-aligned training and editing services.